Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

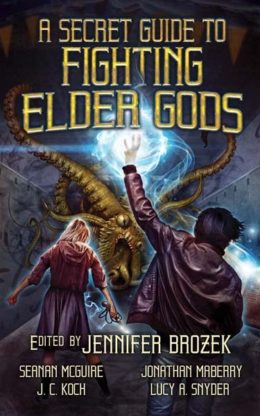

This week, we’re reading Seanan McGuire’s “Away Game,” available April 16th in Jennifer Brozek’s A Secret Guide to Fighting Elder Gods anthology. Spoilers ahead, but only minor ones—we don’t want to give more than a teaser for a story that isn’t yet available, so if you want to find out what happens you’ll just have to read for yourself!

“I’m asking for a friend who’d really rather not wind up missing the football game in order to star in a horror movie.”

Summary

A gray autumn drizzle isn’t enough to quench the enthusiasm of the Johnson’s Crossings Fighting Pumpkins—not when they have an away game that evening. The football team runs scrimmages on one end of the field, while the cheerleading squad polishes its routines at the other. They are no ordinary squad. However comforting ordinariness might be, the Pumpkins can’t afford that luxury.

When squad captain Jude allows herself to, she takes strongly after her mother, especially in her teeth. And her willpower.

Sarcastic, intrepid Heather can help support a pyramid of girls. Her sense of smell is animal-keen and when provoked, she moves with the predatory grace of a lioness.

Sweet-natured Laurie runs on intuition, and a voice that can command obedience. Good thing she’s so damn nice.

Colleen is as much at home among rulebooks and tomes as she is flipping and spinning midair. Historian of the group, she knows that “writing things down is a protection against an uncaring universe, as long as you’re sure nothing’s changing what you wrote.”

Along with the rest of the squad, the girls work as a single entity, ready to inspire their team to victory, or to walk into danger with pom-poms held high. And danger seems likely in the odd little town of Morton, home of the Black Goats. The trees there grow twisted, like tortured dancers “wrapped in gowns of bark.” Morton High School is a campus of paths and buildings subtly distorted, as if there’s “some intangible, indefinable problem with the way the corners come together.”

As Laurie puts it, the walls are just wrong. And Jude senses that Morton belongs to… something. The town isn’t big enough to encompass what owns it, and so that thing only fully manifests when the time comes for the town to pay tribute.

The visiting team and its cheerleaders are none too keen on being part of that price…

The Degenerate Dutch: No degeneracy this week—though Morton looks like exactly the sort of hyper-rural town that gives rural towns a bad name (and an association with a certain sort of horror movie).

Mythos Making: In addition to the Black Goat With a Thousand Young Football Players, “Away Game” features the more obscure Yibb-Tsill, a nightgaunt patron created by Brian Lumley and notable for having sufficient breasts to feed them all. Inquiring minds want to know how critters with no faces manage to suckle at deific teats, no matter how numerous.

Libronomicon: Colleen, the team’s record-keeper, is also their specialist in dealing with eldritch tomes and esoteric school regulations (which may have more overlap than you’d expect).

Madness Takes Its Toll: The Goats play a lot of mind games to get their victims where they want them, and to keep everyone else driving in circles elsewhere.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’ve been wanting to read more YA Lovecraftiana ever since getting a taste through my co-blogger’s work. It’s a natural fit: What is young adulthood if not a period of emotionally intense adjustment to an uncaring universe? Of railing against the general unfairness of existence—and trying to do something about it? So I was delighted to get an ARC of Jennifer Brozek’s soon-to-be-released anthology A Secret Guide to Fighting Elder Gods. I think this marks our first time covering work that isn’t actually out yet; in the absence of reliable time travel you can catch up on April 16th.

Another natural fit is cosmic horror and cheerleaders. This was maybe not entirely obvious when Buffy the Vampire Slayer first came out, but I was about Buffy’s age at the time which means Buffy is now my age, and I hope we’ve all long since learned our lessons about messing with women who can jump that high while wielding sticks. Not to mention who can work in teams. In a genre where people all too often go solo, or work in pairs with domineering terrible-idea partners, teams are likely to massively improve your survival rate.

“The Thing on the Cheerleading Squad” gave us Innsmouth’s cheerleaders, but their teamwork played out mostly in providing the emotional support that Asenath so badly needed. They weren’t actually dealing with her father directly—though things might have gone rather better if they were. The Fighting Pumpkins take a more active role in these things. When they’re working together, they’re a beast in their own right, ready to tear at the sky, and woe betide anything that gets in their way.

A third and final natural fit is cosmic horror cheerleaders and Seanan McGuire. (Much like scary aquatic humanoids and Seanan McGuire, a combination we’ve appreciated previously.) Throw in a Halloween-themed school district full of teams of Pumpkins and Scarecrows, and the only thing missing is a corn maze for catching any eldritch beastie foolish enough to wander into the wrong horror subgenre. There is so much love in this story: for all the corners of horror, for teams of girls, for victims who fight back as champions, for all the victims who didn’t have the power to do so. Somewhere in the middle of the story, while they’re trying to figure out non-Euclidean architecture, my notes read: “This is not, in fact, a normal cheerleading squad. Unless all cheerleading squads do this.” Which, y’know, seems increasingly plausible.

“Away Game” introduces an ensemble that seems ready for many more stories. I’m intrigued by them all, but my personal favorite is Colleen. While her squadmates are busy rocking dhampyr bloodlust and endurance, or being She Who Must Be Obeyed, she’s… taking notes. Making sure no one is messing with their memories. Figuring out the exact timetable of goatish sacrifices. I always have a soft spot for the librarians, and especially for combat librarians who can come up with the precisely needed fact to get everyone safely through an action scene.

I’m also awfully fond of Laurie, who Must Be Obeyed. That seems like a power that could be awkward as often as useful, if it can’t be turned off.

All together, I’m hoping to see more of the Pumpkins at work—and nearer term, I’m looking forward to reading the rest of this anthology, which couldn’t have picked a better opening act.

Anne’s Commentary

In her anthology A Secret Guide to Fighting Elder Gods, Jennifer Brozek has collected thirteen Mythos stories told from “a youthful perspective,” that is, by teenage narrators. I like that her foreword dodges the label “young adult”; while I acknowledge the marketing utility of such age-based labels, I find they’re often misleading. Or maybe self-limiting would be a better word. No news to anyone who follows SFF—or to anyone who glances at bestseller lists—that middle-graders weren’t the only ones devouring Harry Potter’s adventures and that adults were all over YA series like Twilight and The Hunger Games. Brozek goes on to summarize the anthology’s premise:

In truth, there is no greater zealot than a teenager who believes; who has seen the light or the darkness and knows what goes bump in the night. It is these teenagers who will save or destroy us.

Zealots like Joan of Arc and Buffy Anne Summers! Is there any age limit to those who can fall engrossed into their stories? I don’t think so, and I don’t think there are generational impediments for readers of Brozek’s Secret Guide. We all are or will be or have been teenagers. We therefore know or can anticipate or can remember the travails, triumphs and disasters that give adolescent protagonists such powerful potential. Adolescence is a life phase necessarily fraught by change; change is the prime mover of narrative, for it entails opportunities to be seized or squandered, hazards to overcome or succumb to. Change kindles feelings of vulnerability, as well as compensatory senses of invulnerability. Teenagers, yeah. Or young adults, if you will. Which, according to the World Health Organization, expands the “young people” range from ten to twenty-four.

I’ll let WHO argue with marketing professionals about that. I want to talk about why the Mythos is a fertile field for YA fiction. If I (and many Reread followers) are typical, a lot of Mythos fans started early. Why not? Lovecraft and Friends wrote, and write, stories that push big fear buttons for boys and girls of every age. That would include the “real” boys and girls, but also those of us who remain boys and girls in emotional memory.

What’s the Mythos got? Let’s start with the unknown. The BIG UNKNOWN. A universe crawling with other life forms and intelligences, to many of whom mankind is a technological/magical inferior, nothing more than bipedal bugs, even. A universe masking other universes, other dimensions, places and creatures beyond our limited understandings, like the mysterious and dangerous worlds beyond grade school, beyond high school, beyond college, into adulthood. Mythos worlds and real-life worlds are ruled by beings of godly power. Can we (should we) placate them with worship and subservience? Can we (should we) oppose them? Is any sort of alliance possible, or at least detente? Or should we retreat into the comfort of “medieval” ignorance, definable here as perpetual adolescence?

Youth isn’t all about fear, though. It’s also about hope, exuberance, outright cockiness. It can experience the WONDER part of the BIG UNKNOWN as well as its terror. On the side of light, wonder could lead to, oh, marvelous travels with the Yith or Mi-Go and/or a tenured professorship at Miskatonic University. On the side of darkness, it could lead to participation in cults and/or black wizardry and/or (of course) insanity. Schmoozing with Nyarlathotep could go either way, just saying.

Then there’s the big connection. Adolescence is about change. Often scary change. Scary change that may work out in the end. Or not. Well, CHANGE haunts the Mythos. There’s CHANGE on a macro-scale, driven by deep time: species evolving and going extinct, civilizations rising and declining, races migrating from world to world. Still more pertinent to adolescence is CHANGE on the micro-scale, individual change. Bodily change, mental and emotional changes. Talk about anxiety-provoking. And Howard himself is way into this theme.

Look at how many times Lovecraft’s people start out fine as children, only to fall prey to the tyranny of genetics and maturation. Arthur Jermyn can’t escape his white ape ancestry, nor can Martenses their subterranean cannibalism. The last de la Poer needs only the environmental trigger of returning to his ancestral home to descend through the centuries of his kind to dining on a plump friend. Pickman must go from painting ghouls to being one. Once his genotype expresses into a piscine-batrachian phenotype, the narrator in “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” must return to the sea or languish in some asylum for freaks. The older he gets, the more Wilbur Whateley resembles his Father.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Pickman and Whateley were apparently always fine with their fates. The “Innsmouth” narrator is the most fascinating of Lovecraft’s “changers,” because his attitude toward bodily change evolves from shock and self-revulsion to acceptance. A total conversion, actually: To grow from human to Deep One is a glorious outcome.

What an encouraging parable for teenagers! In a twisted way, so too is the most teen-angsty of all Lovecraft’s stories, “The Outsider.” The narrator grows increasingly lonely and claustrophobic in his forest-oppressed castle. He’s been stuck in his parents’ basement too long! He needs a social life, mingling among the gay crowds he’s seen pictured in dusty old (YA?) books! So he climbs the castle’s loftiest tower (here’s that towerly phallic-vaginal imagery again) and pops out in—a graveyard. How Goth is that? No matter, he soon finds another castle in a wood, but one where a superbly gay party is in progress. Here’s his chance to crash the prom and prove himself a worthy reveler! Too bad his adolescent self is so hideous, everyone flees. Too bad he can’t pretend it was some other hideous prom-goer that scared them off. The bane of insecure teens everywhere, a mirror, stands before him, proving he’s the monster. Pretty much dead and rotted, in fact.

No problem in the end. He returns to the Goth graveyard and meets other Goth ghouls. At last, among his own people, his forever bros, he can be himself and have one hell of a time riding the night-wind and playing amongst the catacombs of Nephren-Ka.

I love me a bittersweet ending to a young person’s tale. Maybe the stalwart cheerleaders in McGuire’s story will have one, despite the hovering menace of a certain Black Goat. As Brozek writes of them and the other teenagers in Secret Guide, “Sometimes they win. Sometimes they lose. Sometimes… they give in to the temptation of power.”

Sounds like a harrowing fun ride to me.

Next week, we tackle Lovecraft and Wilfred B. Talman’s “Two Black Bottles,” and the further perils of necromancy.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.